The week is just starting, but already the news has not been good for the American consumer. Yesterday CNN ran a story, “When Credit Puts You in Jeopardy,” which cited a Demos study showing that overall credit card debt grew by 315 percent from 1989 to 2008. In addition, CardTrack.com is reporting that the percentage of people who are delinquent on their credit card payments is the highest it has been in three years.

Then comes the news that foreclosures were up 57 percent in January over the same month last year. If there was any good news in this report it was that the month-to-month increase in foreclosure had diminshed slightly, but it is clear the foreclosure crisis will continue. Yesterday also brought news that sales of existing homes dropped for the sixth straight month and that prices are continuing to decline. As long as the real estate market is in free fall, more and more people will find themselves trapped in a house that is worth less than the mortgage. If they, like millions of others, get into a financial squeeze, selling the home to get out from under the mortgage will not be an option.

So many people are facing foreclosure that a new cottage industry has cropped up. You Walk Away is a web-based company that sells a “Protection Plan and Kit” to help homeowners through the process of foreclosure. Critics argue that this kind of business is changing consumers’ moral compasses and encouraging irresponsible behavior, but it seems to me that both irresponsible lending and irresponsible escape from obligation are the natural results of an unregulated free market system. The NPR site has a good story on this issue.

On the heels of these discouraging reports comes the news that two bills that would provide relief to holders of subprime mortgages are under attack by the mortgage industry. For a counterbalancing defense of the bills, see Elizabeth Warren’s most recent blog posting.

Finally, today CNNMoney.com is reporting that consumer confidence is at its lowest point in 14 years. In a consumer-driven economy that is very bad news indeed.

Meanwhile, as I write this the Dow Jones Industrials average is up 126 points (1.01%) on the day. Go figure. It seems to me that, more than at any time in recent history, consumers and investors live in two different worlds--worlds that are often in direct conflict. I will have more to say about this in a future post.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Still Going Broke

Monday, February 18, 2008

Something Happened in the 1970s: The Minimum Wage in Perspective

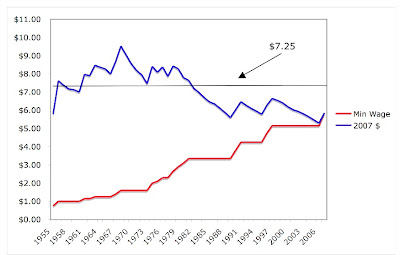

While looking at some data on the US federal minimum wage, I came across an interesting trend. One of the themes of Going Broke is that something happened in America beginning in the 1970s. The symptoms were dramatic increases in rates of bankruptcy and personal indebtedness that continued right into the 21st Century, but the causes of these signs of soaring of financial misery are far from obvious. I make a case for the combined effects of several modern pressures, and one of these is economic insecurity produced by declining real wages for many workers. Now take a look at the graph below, which I constructed a few days ago.

The red line of the graph shows the actual or “nominal” minimum wage for each year since 1955, and the blue line shows that wage, adjusted for inflation, in 2007 dollars. So, for example, in 1979 the minimum wage was $2.90/hr but it had the equivalent buying power of $8.28/hr today. The overall arc of the blue line shows that, here, too, something happened in the 1970s. From 1955 through 1968, the minimum wage rose sharply, peaking out at $9.53/hr (adjusted for inflation) in 1968, but since the late 70s, the minimum wage has been on a long and jagged slide.

Last year, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the Democratic congressional victory of 2006, Congress and the President agreed to a plan to increase the federal minimum wage. Under the new law, the wage will increase in each of three years, topping out at $7.25/hr in the summer of 2009. The graph shows that, when the minimum wage hits this point, it will bring us back to where we were in 1982, when the nominal minimum wage was $3.35/hr. Of course, this really overestimates the increase, because by the time the summer of 2009 rolls around, inflation will undoubtedly have increased, pushing the black horizontal farther down relative to the blue line.

Most states have set their own minimum wages at rates higher than the federal rate, but as this map from the US Department of Labor shows, there are 18 states (blue, red, and yellow below) for which the federal minimum wage applies, including Louisiana and Mississippi, the states most severely affected by Hurricane Katrina. Economists argue about whether increasing the minimum wage has the negative effect of increasing unemployment. But we know that income disparity has increased over the last three decades, and it seems likely that this trend in the federal minimum wage has been a contributing factor.

Thursday, February 7, 2008

Will We Begin to Spend Less and Save More?

A February 5, New York Times article “Economy Fitful, Americans Start to Pay as They Go” predicts the credit crunch and downturn of the housing market will lead Americans to use credit less and save more. Writer Peter Goodman points out that many people who have been spending out of their home equity will now enter a period of forced restraint. The free ride produced by rising real estate prices and easy credit has come to an end.

Without question, many who could spend freely in the past will now be constrained by lack of equity, but if credit card debt remains as widely available as it has, the basic problem—our spending-to-savings ratio—may persist. My mailbox still contains daily credit card solicitations, and at the mall I am regularly offered store credit cards. As long as the use of credit cards is so widespread, we are likely to have a continuing problem with debt. In a service economy dependent upon consumerism, many people will respond to the impulsive voice in their heads saying, “Put it on plastic,” rather than the wise one saying, “Don’t buy it. Save your money.”

In addition, saving has gone so far out of fashion that there are few social or economic incentives for holding on to your money. If we are going to wean ourselves from plastic and protect ourselves from the uncertainties ahead, we need to create easy mechanisms for putting income away and do a much better job of selling the virtues of a well stocked savings account.

Friday, February 1, 2008

Medical Innovation is the Mother of Health Care Necessity

Some things are just wants. Products or services that we would like to have—sometimes really like to have—but we know we can live without. Often these desires are created by product innovation. Steve Jobs introduces a new iPod or the iPhone, and suddenly we have wants we could never have imagined.

In The Overspent American Juliet Schor describes the gradual ratcheting up of needs. Home air conditioning was once considered a necessity by very few, but now fully 70 percent of us consider it a need. Because few of the old needs go away, technological advances create more “needs” that compete for our income. Just a few years ago, computers and cell phones were unheard of, and now they are must-have items.

But sometimes a new product becomes an immediate need. The minute it is introduced we have no choice but to buy it. This is particularly true for medical treatments. Health is the trump card. In Going Broke I give the example of Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering statin drug, that, once introduced, became an instant necessity for millions of Americans. In 2006 Lipitor’s US sales were 12.9 billion dollars, making it was the highest-selling drug in the world. If you have high cholesterol that you are unable to bring down any other way, your doctor is very likely to prescribe Lipitor or a similar drug, and most consumers will fill the prescription because they feel they must. You can’t take chances with your health.

Now the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has produced a report, “Technological Change and the Growth of Health Care Spending” showing that approximately half of the growth in US health care costs in recent decades comes from medical innovation: new treatments made possible by technological advances. Furthermore, the report concludes: “The nation’s long-term fiscal balance will be determined primarily by future growth in health care costs” (p. 17). This is a big problem fraught with ethical issues. How do we apportion medical services and who should pay? Medical innovation is a two-edged sword. It brings the hope of longer life and better health to many, but it also hungrily consumes more and more of our personal and national budgets. Where will this trend lead us?