An unanticipated effect of the economic downturn: recyclables with no place to go. As the economy tanks, the demand for recyclable cardboard, plastic, and metal has fallen away. According to a front page article in yesterday’s NY Times, the market for junk has collapsed at a far more drastic rate than the stock market. On the West Coast, mixed paper that was bringing in $105 a ton in October now sells for $25. The recycler that Harvard University sends its junk to used to pay $10 a ton but now charges $20 a ton.

Our recycling system is a house of cards built on consumerism, a system that puts all its energy into the front end of the purchasing sequence. The crucial moment is when the shopper lifts the bottle of juice off the shelf and into the shopping cart. The more the bottle weighs, the fewer units will be sold. Fifty years ago, Sylan Goldman, a grocery store owner in Oklahoma, noticed his customers left the store when their hand baskets were full. To subvert this limitation, he mounted two hand baskets on a folding metal frame and thus was born the shopping cart.

Manufacturers and retailers understand the physics of consumption. The physical effort of a purchase strongly affects sales. For people in cars, drive-thru windows are easier than walking. So when it became possible to package products in inexpensive, light plastic containers, manufacturers switched. Glass bottles were ditched in favor of plastic “recyclable” containers, many of which now overfill our landfills. Business people know that maximizing consumer convenience maximizes profits. Furthermore, the life of the container after the product has been consumed has no affect on the manufacturer’s bottom line. Unless producers are required to bear the cost of recycling or storing used containers, this is a negative externality: a cost of production borne by someone else.

Interestingly, the Times article notes that demand for glass has not declined. According to Wikipedia, glass and aluminum are much easier to recycle than plastics. Both can be recycled indefinitely. Perhaps this is the moment to bring back reusable and recyclable glass and aluminum containers. They would have the dual effect of decreasing consumption—at this point in our history, a very desirable goal itself—and reducing the size of our junk heaps.

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

The Detritus of Consumption

Thursday, October 23, 2008

The Myth of Establishing Your Good Credit

One of the standard maxims mouthed by personal financial advisors is the need to establish your good credit. Young people are advised to get a credit card and use it, being careful to pay off the balances regularly, with the goal of creating a good credit record. The person who fails to do this is said to risk not being able to get a house in the future or achieve any number of other goals.

This has always struck me as crazy advice. First, it puts young people at risk of doing the opposite—getting into trouble with credit cards—in the name of a rather abstract goal. Second—and most importantly—for many years now there has been little problem getting credit. Indeed the problem has been the availability of too much credit. At the end of the housing boom, people were able to get home mortgages without having any assets or income, and anybody can get a credit card with a shockingly high credit limit. When I interviewed debtors for Going Broke, many told people me they continued to receive credit card offers after declaring bankruptcy and had little trouble getting credit. So why is it so important to establish good credit? Perhaps this was a valuable goal in the bygone era when lenders actually cared about the credit worthiness of their customers, but a loan is no longer a social bond. It is merely a product to be sold for a short-term gain.

Given the recent credit crisis and Wall Street tumble, one might assume this picture had changed. Not so. The latest installment in the New York Times debt series documents the continuing—and perhaps increasing—practice of preying upon people who have recently declared bankruptcy. Using sophisticated data mining techniques, banks are targeting people who have experienced recent debt problems with credit card offers. If there is a credit freeze, it has not hit individual consumers. Consumer debt is still a profitable engine for many banks, and the industry is discovering ever more innovative methods of finding vulnerable potential customers.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

The Paulson Bailout Plan: A Profiles in Courage Moment

This may be the most important vote since the authorization of the Iraq war, and in many respects, the atmosphere is similar. Congressional leaders have been churned up by a worsening economic picture and the drama of last Thursday’s emergency meeting with Henry Paulson and Ben Bernanke, where lawmakers were told there was a serious risk of massive failures within days and that casualties could go beyond the banking industry to large “brand-name companies.” Senator Christopher Dodd described it as “as sobering a meeting as any of us have ever attended in our careers here.”

Furthermore, this is an election year, and Congress is set to go home and resume campaigning at the end of the week. So a plan to save the economy and bailout the financial firms that got us into this mess will be hammered out very hastily in the heat of emotion. And, like the Iraq war vote, decisions made this week will haunt us for years.

The amount of money at stake is staggering. $700 billion is more than the cost of the war in Iraq to date, more than the entire 2009 budget for medicaid and medicare, more than the 2009 budget for social security, and just under the 2009 military budget. It represents $2000 for every man, woman, and child in the country--above and beyond what we already pay for the actual services of the federal government. And for what? To keep us all from being damaged even more than we have already by the irresponsible business practices of the financial industry we are bailing out.

The great majority of our leaders failed us in the Iraq authorization vote. They made political decisions based on the emotion of the moment. Let’s hope they do better this time. If this deal does not go far enough to reign in the unfettered business practices that got us here, then our leaders must have the courage to walk away. This time, the administration cannot be given a blank check. The deal must provide strong oversight and powerful safeguards against future crises, or we must be willing to say, “No deal.”

Tuesday, September 9, 2008

Homeownership & the American Dream

Home ownership is perhaps the most tangible symbol of the American Dream, but in recent years it has been oversold. Many people who later wished they had remained renters were sold enticing low-interest mortgages. Thanks to an economic downturn, insufficient regulation of the mortgage lending and mortgage investment industries, and good old fashion overconfidence in the security of real estate investments, many of those same people are now headed back to rented dwellings, but too often their path will run through foreclosure.

As the graph below suggests, the US experienced a rapid acceleration in home purchases beginning in 1992 and topping out at 69 percent in 2003. Since that time the rate has declined to the present 68 percent, and it may drop further. Recent history suggests the line may have been pushed up too high, and the current economy is making a correction.

There is no reason why the American Dream should be dependent upon home ownership. Internationally homeownership rates vary widely and are not particularly tied to standards of living. For example, Germany, a country that enjoys a standard of living (measured in GDP per capita) of $23,819, has a homeownership rate of 42 percent, whereas in Slovenia (GDP per capita of $19,200) 82 percent of people own their homes. Several of the countries of old Europe (e.g., France, Denmark, Austria) have homeownership rates that are over 10 percent below those of the United States.

Owning your own home is a greater financial risk than many thought, and too much risk can make the dream—when defined as owning your own home—a bad bet. But happiness and security can come in different shapes, and life in a rented home can be just as happy as life in a mortgaged home.

Monday, August 25, 2008

Joe Biden & MBNA

I am a strong supporter of Barack Obama’s campaign, and I am very pleased with his selection of Joseph Biden for Vice President. Biden will bring needed experience, respect, and fire to the campaign. But Joe Biden is from Delaware, the home of MBNA, the credit card giant, now owned by Bank of America.

All politicians have warts of one kind or another, and as a citizen it is all but impossible to find a political leader with whom you always agree. But as someone who is concerned about Americans who struggle with debt, I find Biden’s stance on bankruptcy reform particularly troubling. He has been a consistent supporter of the credit card industry’s efforts to make bankruptcy rules more stringent and to make the process of declaring personal bankruptcy more onerous and more expensive. After nine years of lobbying, the banks were able get a new, tougher bankruptcy bill through Congress, and President Bush signed it into law in 2005.

Barack Obama voted against the bankruptcy bill and has been a steady opponent of the credit card industry, but Biden’s stance on this issue is a blemish on an otherwise very respectable voting history. Unfortunately, now that the economy is in a tailspin and foreclosures are bursting out all over, the hurdles imposed in the 2005 bankruptcy bill are making life even more difficult for many debt-burdened consumers who could use the second chance that bankruptcy is designed to provide.

To make matters worse, there is at least the appearance of an improper relationship between Biden and MBNA. Today, the NY Times is reporting that Hunter Biden, the senator’s son and an attorney, worked for MBNA for from 2001 to 2005, a period that coincides with the credit card industry’s bankruptcy lobbying effort. The Obama campaign is defending this messy bit of Biden history, but it is a troubling episode that provides yet another example of the pernicious influence of big money in our government.

Friday, August 22, 2008

Appearance on The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer

As part of series conversations on the economy, I appeared on the Monday, August 18th edition of The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. A transcript of the interview, as well as audio files and streaming video can be found here.

Sunday, August 10, 2008

Exporting Credit Card Debt

I am often asked why credit card debt is such an American problem, and my usual answer is that, with some exceptions, other countries haven’t caught up with us yet. We lead the pack in indebtedness. The latest installment in the NY Times series on debt shows how the rest of the world is catching up. For some time, the UK and its former colonies (US, South Africa, and Australia) have had debt problems, but now credit cards, and the problems associated with them are spreading to Asia and Latin America. The article highlights problems in Turkey and South Korea.

Few American exports have proved as popular as credit cards. In just a generation, they have gone from a totem of Western affluence to an everyday accessory in Brazil, Mexico, India, China, South Korea and elsewhere. More than two-thirds of the world’s 3.67 billion payment cards circulate abroad.

The world map displayed below shows an expanding pattern of debt. Most of the light areas that have no debt are third-world countries where poverty is so desperate that credit cards would have no purpose. As time passes, this map is likely to go in one direction only: toward darker shades of green and increased credit card debt. It is troubling to think of a future world economy in which every developed nation has a citizenry strapped with debt and chained to their jobs in an effort to meet their monthly obligations. Is this an export the rest of the world really wants?

Tuesday, July 29, 2008

Pay With Two Credit Cards

Today I ordered an accessory from the Apple Computer website and noticed something I had not seen before. During the checkout process a “pay with two credit cards” button appeared. Curious, I clicked the button and discovered an option that allows customers to split the cost of their purchases across two credit cards with the flexibility to decide how much of the total to put on each one.

The splitting of online purchases may be more common than I am aware, but this is the first I had seen this option. Of course, Apple sells items that can cost several thousand dollars and, as a result, will often be out of reach for someone with a modest credit limit. Young college students purchasing a computer might not have enough juice in their accounts to handle the bill. But I suspect this payment option is also an indication of the kind of debt-juggling many consumers undertake on a daily basis. By offering the card-splitting option, Apple makes it possible for the buyer who is near the limit on several credit cards to cobble together enough credit to float the purchase of a new iPod or laptop. People who are living this close to their credit limits may represent a relatively small segment of the potential sales market, but from Apple’s point of view, allowing card-splitting is a very simple way to increase sales. Unfortunately, for the consumer who struggling to managing temptation and debt, this system removes one more natural barrier to indulgence.

PS Curiosity has its costs. After clicking the “pay with two cards“ button it took me several minutes to escape from that detour and pay for my item with a single card. Caveat emptor.

Monday, July 28, 2008

Free Markets, Banks, Personal Responsibility, & Self-control

In his column today, Paul Krugman makes the point that the housing bill passed last week and due for Presidential signature this week does not fix an important underlying problem. The bill provides a way for some homeowners to avoid foreclosure by refinancing their adjustable rate mortgages with smaller fixed rate loans, and it will provide additional support for the mortgage backers Fannie and Freddie Mac. But, in a piece called “Another Temporary Fix,” Krugman argues that future problems will not be avoided until and unless new banking regulations are introduced:

The back story to the current crisis is the way traditional banks — banks with federally insured deposits, which are limited in the risks they’re allowed to take and the amount of leverage they can take on — have been pushed aside by unregulated financial players. We were assured by the likes of Alan Greenspan that this was no problem: the market would enforce disciplined risk-taking, and anyway, taxpayer funds weren’t on the line.

And then reality struck.

From a psychological point of view, it is interesting to think about banking regulation and self-control. The pro-business free-market view places great stock in personal responsibility. We are all on our own, and those who fail fail because it is their own fault. In one sense, they are supposed to fail because they are responsible and no one else should have to take the blame. Certainly this is the conservative view of personal debt.

But sometimes personal failures have public effects. Call me a cynic, but I believe there would not be a housing bill but for the fact that the housing crisis affects us all. Everyone’s equity goes down when the real estate market collapses, and foreclosures at the rates we’ve seen are having a profound effect on the economy as a whole. In contrast, personal consumer debt and bankruptcy is a much more private phenomenon. We had over a million personal bankruptcies per year for many years, and yet all those individual tragedies were almost invisible. Now because, innocent people are being affected, politicians have the moral traction to get a bill passed. Of course, many the debtors who face bankruptcy are also innocent victims of a volatile economic environment, but that is another story.

Krugman’s column suggests that businesses, specifically banks, have failures of self-control, too. In a free market environment, failures of corporate responsibility are likely to occur, and regulations are justified to protect us all from the troubles these failures bring. Recently, new financial institutions have sprouted up outside the bounds of existing regulations, and it is, in fact, these institutions that have been source of many of our current woes. Rather than being quietly fixed by the wisdom of the marketplace, these failures have had powerful reverberations throughout the economy.

Problems of self-control abound, for individual consumers and for banks. The current crisis suggests that external controls can be very helpful for banks, just as they are for the rest of us. It is much easier to do the right thing if the environment pushes you in that direction. Where there are inadequate natural constraints in the marketplace, regulations can play a very valuable role, and recent events have reaffirmed the importance of banking regulation.

Saturday, July 19, 2008

NY Times Debt Series

Tomorrow’s NY Times features a very good series on personal debt and, in particular, the changes in lending practices that have earned millions for the banking industry and socked consumers with enormous levels of debt. Some of the interesting bits include:

- Average credit card interest rates have risen from 17.7 percent in 2005 to 19.1 percent last year.

- Average late fees rose from $13 in 1994 to $35 today.

- In the same period, the fee charged for exceeding your credit limit rose from $11 to $26.

- In 1957, 42 percent of families had no debts; today 24 percent of families have no debts.

- In 1957, 53 percent of homeowners had no mortgage debt; today 31 percent of homeowners have no mortgage debt.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Gas & Housing Prices

In Going Broke and in this blog (see the July 7 post below) I have described the post-World War II expansion of suburban lifestyles and the popularization of single-use zoning and single-family homes that were many miles down the interstate from work. Sprawl made us dependent upon our cars to satisfy any need that was outside the house, but the wide use of automobiles also reduced the physical effort of traveling to the marketplace by providing us with moving chairs to sit on in climate-controlled environments. In addition, the popularization of drive-through windows meant that many purchases could be made without getting out of the car. The effects of these trends can be seen in our waistlines and bank balances.

Then came the gas crisis. Suddenly our car culture has become very expensive, and as this video from the urban development group CEOs for Cities shows, gas prices have affected housing costs in suburbia. For many years, houses far out from the city center were cheaper than houses close in. In most areas, that may still be true, but the high cost of gas is turning that equation on its head. The gas crisis did not cause the mortgage crisis, but growing transportation prices have undoubtedly worsened the mortgage crisis in some suburban areas.

Monday, July 7, 2008

How We Made Gas a Necessity

Gas prices continue to be the hot topic. Oil has hit $140 a barrel, and many people are projecting $200 a barrel prices by the end of 2008. As long as gasoline is considered a necessity—something we have no choice but to buy—demand will be relatively “inelastic” with respect to price. The drop off in demand will not be proportional to the increase in price because most people see no alternative to automobile transportation. As a result, we are going to be beaten down by any price increases that come along.

If gas is a necessity, we have ourselves to blame. The Interstate Highway act of 1956 made it possible to live far from work, and single use zoning created towns where housing was segregated from business and retail districts. Finally, FHA mortgage programs favored single-family dwellings over multiple-unit housing. The result was the great suburban expansion of the post-World War II era. Finally, for many years the automobile business was the leading industry in the US, and public transportation systems were discouraged. Today, few of us can walk from our homes to work or even the grocery store, and we are almost completely dependent upon internal combustion engines. Unfortunate, half a century later, both the cars and the fuel are likely to come from abroad, and we have no choice but to buy them.

In the long run, we will be much better off if we go back to a more European style of village- or town-focused life that makes better use of public transportation, as well as foot and bicycle travel. As higher gas prices hit in 2008, demand for gasoline dropped off the more in the UK than in other areas of Europe and the US. Why? Because the British have more alternative forms of transportation. An oil industry analyst quoted in a recent Daily Telegraph article put it this way:

They are switching to public transport, which is much easier to do in Britain than in America, where people living in the suburbs often have to drive whether or not they want to.

Consider also the use of bicycles in the UK. The photograph below is of the train station in Cambridge, England, where commuters deposit their bikes on their way to work in London or elsewhere.

Cambridge is a town of approximately 130,000 people 50 miles northeast of London, and it is thought to have the highest level of bicycle use in the country. According to the 2001 census, 25% of citizens said they used bicycles to get to work each day. With gas prices on the rise, one can only assume that figure has gone up. For Cambridge residence, gas-powered transportation is not a daily necessity.

When Americans have greater choice about whether or not to get into their cars, they will far less vulnerable to fluctuations in the price of a commodity we must by from foreign suppliers. But if we are to create more transportation choices, we will need to make substantial investments in infrastructure, reversing some of the transportation and housing trends of the last 50 years. The good news is that, with a sagging economy, this an excellent time to make those investments.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Loan Delinquencies Spread to Other Forms of Consumer Credit

The economic downturn and home mortgage crisis is being felt in other areas of the banking industry, and the result may be a second wave of bank failures, this time in regional and local banks. In an article entitled, “New Crisis Threatens Healthy Banks,” the Washington Post reports that delinquencies are up in credit card payments (which had been previously reported), home equity loans, and—most strikingly—construction loans (see the Post graphic below). Many smaller banks that avoided the subprime mortgage market are, nonetheless, mainstays of the home equity and construction loan business in their areas. As a result, this spread of delinquencies may lead to problems for these smaller institutions.

Although we were not hearing anything about it at the time, this graph also shows that delinquencies in construction loans actually led the foreclosure crisis. The uptick in construction loan delinquencies appears to begin in mid-2006, which is before the current crisis began. In contrast, the consumer aspects of the crisis hit a year later in mid-2007, just as foreclosures began to soar. The graph below, which comes from econoday.com, shows that mortgage interest rates bottomed out in 2005 and and began to rise in late 2005 and early 2006. New home sales fell accordingly, and delinquencies in construction loans followed.

All of this dramatizes the powerful role of the real estate market in stimulating our current economic difficulties. Of course, once these real estate trends got the ball rolling, our sleeping problems with consumer debt (home equity loans & credit cards) just made matters worse. Much worse.

Friday, June 13, 2008

How Do We Change Values?

On Tuesday of this week, David Brooks had a very good column called “The Great Seduction” about the America’s epidemic of personal debt. The article is based on a new report issued jointly by the Institute for American Values (which concerns itself with marriage and divorce, among other things) and a number of other think tanks, including Demos and the New America Foundation. The report and Brooks’ column make a number of very good recommendations, such as credit card reform, regulation of payday lenders, and programs to promote saving. But at the end of the column Brooks returns to one of his regular themes:There are dozens of things that could be done. But the most important is to shift values. Franklin made it prestigious to embrace certain bourgeois virtues. Now it’s socially acceptable to undermine those virtues. It’s considered normal to play the debt game and imagine that decisions made today will have no consequences for the future.

He is, of course, correct, but the difficulty is knowing how to change values. We can state our values and identify our chosen virtues, much as Franklin did, but merely calling for a kind of behavior does not always do the trick. Values often follow behavior, rather than the other way around. We acquire many virtues by practicing them. Parents model truthful statements, hard work, and thrift, and they reward us for following their lead. Our modern problem stems from those instances—and there are many—when our behavior is molded by commercial and technological developments, and a new and less virtuous value results.

Take, for example, pornography. Once a very seamy commodity consumed by only the most depraved members of the community. To find it, you had to go into parts of town most people preferred not to visit. Then came the VCR. With the introduction of videocassettes that could be watched at home in privacy, many of the social barriers were removed. Distribution took a further leap forward with hotel and home cable systems, and finally, the internet really brought pornography home. The result is that, despite our highly religious society (compared, for example, to Europe), pornography has become much more acceptable than it was thirty years ago. Jenna Jameson has written a bestselling book How to Make Love Like a Porn Star, and the line between acceptable celebrity and unacceptable celebrity has been blurred. Porn has come out of the closet, driven not by a change in values but by a change in technology. Behavior that is popular begins to appear normal. Today, only child pornography is truly beyond the pale.

So the problem with thrift is that debt is the new pornography. Actually the two have come along together. The introduction of credit cards, 800-telephone numbers, home shopping channels, and the internet have served to eliminate many of the natural barriers to indebtedness. We live in a consumer society that depends on spending and has made it easy to act impulsively 24-hours a day. Popularizing thrift as a virtue is important, but unless we also find ways to encourage virtuous behavior, we are unlikely to demonstrate those values. Brooks’ column—and the report upon which it is based—make many good suggestions, but we also need to acknowledge the powerful effect of the contemporary marketplace on our choices to spend and save. If we can make it easier to show virtuous behavior, the change of values Brooks seeks will follow.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

Mortgage Bankers Association: Worst Quarter in Twenty-five Years

According to a new report from the Mortgage Bankers Association, fully 1 in 10 American homeowners are now in foreclosure or behind on their payments. Furthermore, the problems are not limited to the subprime sector but are evident at all levels of the mortgage industry. Many borrowers with previously perfect records are now falling behind on their payments. In the first quarter of this year, 2.47 % of homes were in foreclosure, up from 2.0 % in the previous quarter. The mortgage crisis has not yet hit bottom.

So where is the response? Where is Ben Bernanke? Where is Congress? Where is the President? Bear Stearns was an instant, over the weekend bailout, but when it comes to the problems of everyday homeowners, you're on your own. We’ve got an 800-number for you, but beyond that we’ve got a big nothing.

Friday, May 30, 2008

The Arbitrary Pricing of Branded Products

Yesterday’s NY Times ran a story in Thursday Style called “Dress for Less and Less.” The article’s premise is that, despite rising prices for food and gasoline, the cost of clothing has gone down. As examples, the author, Eric Wilson, cites Levi 501 jeans that were $50 in 1998 and are $46 2008 and Lacoste polo shirts that went from $95 to $75 in the same time period.

It is difficult to take such a story seriously. All the products mentioned are highly branded, in most cases high-end or designer goods (Vuitton, Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers), and quite expensive. Most middle class shoppers will not be paying $325 for a DVF wrap dress, and I have never paid even half of $75 for a polo shirt. But the interesting question is why? Why have these clothing prices come down? Wilson gives two explanations:

Over all, apparel prices have gone down primarily because of two factors: the overwhelming movement of manufacturing to countries with cheaper labor, where the clothes are made, and increased competition between traditional retailers and discounters, where the clothes are sold.

The outsourcing of jobs provides savings for all clothing manufacturers, and the article does not assert that discount prices have moved down to a similar degree. So the answer is price competition. Cheaper non-branded goods are being offered by discounters, and, in some cases, discounters are selling the same items for less. The elasticity of price for these more expensive products reveals the premium we pay for brand name goods and how arbitrarily manufacturers and retailers set their prices. Despite somewhat lower prices today, we can assume these branded items are still profitable—else they would not be sold. The profits are just a little smaller than they used to be.

Friday, May 23, 2008

The Psychology of Netflix

The spending response is strongly affected by two variables: effort and time. The Netflix system of DVD rental by mail has succeeded by reducing both. Before Netflix, renting a movie required a trip to the video rental store, which took both time and effort. Ordering online meant that by planning ahead you could always have a movie on hand, so you could watch a movie without going out to get it. Furthermore, Netflix’s enormous selection and sophisticated searching and recommendation system make it much more likely you will find movies you really want to see.

The one drawback of the Netflix system is that you cannot be completely impulsive. The movies you order come in the mail, so at very least, your viewing selection must take place a day or two before you watch. You have to plan ahead. Finally, even if you have one of the Netflix plans that allows you to have several movies on hand at a time, a serious weekend movie binge can burn through your stack of DVDs, forcing you to wait until the postal service has time to replenished your supply.

So Netflix is an incompletely impulsive indulgence. You cannot make a movie choice on a whim, click, and immediately start watching, but several companies have been working on this “problem,” wrestling with various technical hurdles in an effort to provide their customers with unfettered indulgence. Yesterday, the NY Times reported that Netflix will now offer a $100 box that will connect to your television and allow downloading of good quality movies over the internet. You use your computer to do the ordering, but you watch the movie on your TV. For those who use it, almost complete impulsivity will be possible. If a friend tells you that you should see a particular film you have never seen before, you can begin watching it in a matter of seconds. Furthermore, once you have purchased the box, you will be able to view as many movies as you want without extra charge. The service will be a free feature of your Netflix subscription and there is no limit to the number of movies you can watch. So, although the thought of the ultimate couch potato, endless weekend movie binge is a bit worrisome, it will now be possible. No need to get out of your pajamas.

For Netflix, the advantage of this system is protection against losing customers to Apple or Tivo, but the effect of this innovation (do we call this progress?) on the consumer will be more movie-watching. The pause in the action created by the postal system will be stripped away, and impulsive and completely uninhibited movie indulgence will be possible. Is this a good thing? Yes and no.

Monday, May 19, 2008

Media Packaging of Good and Bad Economic News

No matter how bad it gets, there are always experts out there willing to put an upbeat spin on the economy, and the media seems to have a bias in favor of positive economic news. In local news, “if it bleeds, it leads” is the defining rule, but when it comes to economic news, we always want to hear that things will be just fine.

Today the CNN webpage is running an Associated Press article with the headline “Economists see credit crisis nearing end,” a happy thought, indeed, but the first paragraph is much less cheery:

WASHINGTON (AP) -- First the good news: The worst of the painful housing slump and the credit crunch might come to an end this year. Now the bad: The economy will weaken further and unemployment will rise.

Like this passage, much of what follows in the article, based on a report from the National Association for Business Economics, is just as mixed. Again, the more optimistic view of the “credit crunch” is really a statement aimed at investors and business people hoping to find money to borrow. There is no “credit crunch” for everyday folks. Instead, there is a debt crunch, and the article predicts increasing unemployment and, to make matters worse, reports that economists are uncertainty about whether housing prices will hit bottom by the end of the year.

The real world for most consumers is hinted at in a paragraph added at the bottom of the article. CNN’s “ireport” team makes the following appeal:

Are you buried under a pile of debt and need help getting out? Did you recently manage to pull yourself out of debt and want to share your story? Tell us about your experience with debt and how the current credit crisis is affecting you. Send us your photos and videos, or email us to share your story.

Personal debt is still a hot story line because there is so much of it out there, but it would be nice to put a happy spin on a dismal circumstance. So please send us a few success stories.

Thursday, May 15, 2008

Consumer Choice: Dumping Starbucks and Whole Foods

As people begin to feel pinched, it is interesting to see how the retail economy is affected. Where are consumers cutting back and—equally as interesting—where are they not? Earlier in the month we heard that Starbucks had experienced a 21% drop in earnings. If there is a single suggestion that personal finance advisors give so often that it has become laughably hackneyed it is to stop buying coffee at Startbucks. “Those latte grandes add up.” Well, it would appear that someone has been listening. Many other coffee options are available, and even without going so far as to brew coffee at home, the caffeine addict can easily steer clear of Starbucks and find cheaper beverages nearby. Demand for Starbucks coffee is highly elastic. Similarly, Whole Foods is experiencing a significant slump. When the going gets tough, higher-priced organic foods look like a luxury.

On the other hand, discounters are doing quite well. Walmart and TJMaxx are expected to show very good earnings. All of this points to a shift in consumer choice that provides clear evidence of an economic down-turn.

Thursday, May 8, 2008

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

Continuing Mortgage Woes

The stock market may be leveling out for now, but as the New York Times reports today real estate prices continue to plummet. Now there are new concerns about mortgage backers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These corporations were created by Congress but are privately owned, and in recent months they have been providing some stability to the shaky mortgage market. Now there are new concerns that Fannie and Freddie do not have enough cash on hand to secure their investments and have been using questionable accounting practices in an effort to satisfy shareholders.

Because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are independent of the government, no taxpayer funds are currently obligated in any collapse of these institutions, but given their importance in the mortgage market, it is unlikely the Fed would just stand by. As Charles Duhigg, author of the Times article, put it: “ if Fannie or Freddie fail, taxpayers would probably have to bail them out at a staggering cost.” That phrase “staggering cost” is more than a bit worrisome. The graphic accompanying the Times article (see below) shows that Fannie Mae’s liabilities alone include $2.1 trillion dollars in mortgage guarantees and another $800 billion in outstanding debt. Freddie Mac holdings are similar. Yikes!

So, we are not out of the woods yet, and other shoes may drop before the subprime mess bottoms out.

Monday, May 5, 2008

Today in Krugman

Today Paul Krugman sums up the current state of the financial markets in a column called “Success Breeds Failure.” He attributes the recent market panic to the introduction of new financial instruments by institutions that escaped regulation because they managed to avoid being banks. Operating in a new frontier, these institutions took great risks, and when things began to come apart at Bear Stearns, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke was forced to act quickly.

Krugman praises Bernanke’s response to Bear Stearns and credits him for what appears to be the current stabilization of the market. But Krugman also worries that the motivation for much needed regulatory oversight has ebbed away with the crisis and that, as a result, the next debacle will be much worse. Krugman is undoubtedly correct. We seem to live in a political-financial world that responds only to today’s financial drama, and the financial services industry, believing that everything has worked out OK, is back to vigorously fighting the threat of regulation.

Of course, stabilizing the market is only one part of our current financial problem. Those who are not in the investment class are still losing their homes and jobs in great numbers. Where is the relief for them?

Friday, May 2, 2008

Why is the Fed Attacking Credit Cards Now?

This morning the Washington Post reports that the Federal Reserve, which has previously been reluctant to regulate the credit card industry, has announced plans to eliminate many abuses, such as universal default. Credit card bills have been introduced in both houses of congress and hearings were recently conducted in the House of Representatives. So now federal-level attacks on the industry are coming from three directions.

Why is the Fed taking action (or promising to take action) now? First, consumer anger about credit cards has been building for some time, and the subprime lending crisis has drawn attention to the problem of predatory lending generally. Second, I suspect the Fed is also responding to criticisms that its recent bailout of Bear Stearns was a big, expensive move that served the upper end of the economy—Wall Street investors—and did little for consumers who happen to be really hurting as real estate values plummet, gas prices skyrocket, and a recession looms. So here was an issue that has suddenly become rather uncontroversial, and the promise of action now might polish the Fed’s image with consumers. They might have waited to make this announcement until the end of the year, when the details of the regulations “could be” finalized, but the Fed needs some image enhancement now.

Rep. Carolyn Mahoney (D-NY) expresses considerable skepticism about the seriousness of the Fed’s resolve. She has recently introduced a Credit Card Holders’ Bill of Rights in the House, and she is undoubtedly concerned that the Fed’s actions will take votes away from her bill. Worst case scenario: regulatory bills do not pass through congress, and the Fed’s actions end up being an inadequate response to the problem. A reasonable concern.

What is the least surprising aspect of this story? You guessed it, the credit card companies object.

Monday, April 28, 2008

Our Future Financial Selves

Today NPR’s Morning Edition carried an Interesting report on debt (you can find the story and audio here). Economist and Financial Times reporter Tim Harford described credit and saving in terms of our future and present “selves.” Harford said: "Debt is your future self sending you money back in time.“ (Economist Thomas Schelling also uses the symbolic conflict between our current and future selves to describe problems of self-control.) Harford gets at the crux of the issue when he goes on to say: ”So the question is, are you and your future self both happy with the deal?“

Only your present self is in the position to make decisions and take actions, and yet the choices you make in the present often obligate your future self. So what would we say about all those financial decisions looking back on them with the wisdom of the future? Harford also described saving as your present self sending money to your future self, and argued that it is possible to save too much (when you have little income). Unfortunately, not being able to save enough, rather than too much, is the problem for far too many Americans. But Harford is exactly right when he says the challenge is to find the right balance between the needs of our present and future selves—a particularly difficult challenge in a world as uncertain as this one.

Something Happened in the 1970s Redux. The graphic below, which was posted on the NPR website to accompany this story, shows two interesting things. First, as I discussed in an earlier blog entry, the real uptick in consumer debt begins in the mid-1970s. This would be even easier to see if the graph extended farther to the left, perhaps beginning in 1950. Second, because the graph superimposes periods of economic recession, it shows that consumer debt often increases even in bad economic times. This is particularly obvious in the most recent recession of the early 2000s, but it can also be seen in the period of 1981-83. We have a troubled relationship with debt that transcends the current economic environment.

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Indian Debt Collectors & More

Today’s New York Times has an article by Heather Timmons about debt collection agencies using phone banks in India to make calls to delinquent credit card customers in the US. Delinquencies were up to 4.5 percent of accounts in the fourth quarter of 2007, from 3.5 two years earlier. Foreign collections calling represents a small fraction of the overall collection business, but bill chasing is just the latest industry to be outsourced to India. These are boom times for the financial misery business, and the influx of well-paying call center jobs has created a group of Indian workers who, as Timmons writes, “are amassing some of the status symbols that probably got their clients into trouble in the first place— new scooters, iPods, Swatch watches and exotic vacations.”

The movement of collections jobs to India is news, but the article includes a couple of other points that I find much more interesting:

- Collections agents are targeting customers’ economic stimulus package rebate checks. On the one hand, this sounds like a ruthless collections technique. You know the debtor is expecting a windfall, so you ask him or her to turn that money into a payment on a credit card. On the other hand, this is precisely what these people should do with their rebate checks. The stimulus package is supposed to be a bit of fuel for the consumer economy, given out in the hope that people will continue spending. But spending is what got delinquent credit card customers into trouble, so they would be much better off paying down debt. This won’t help the economy, but debt-ridden consumers have already done more than they can afford for the sake of the economy. It is time for them to take better care of their personal economies. Collections callers are a hated group who often employ abusive and unethical techniques to track down and intimidate their prey, but here is an unusual case where the interests of both the collection agency and customer are in concert.

- According to Timmons’ article, industry analysts are seeing a new trend: “People are walking away from their homes and hanging on to their credit cards, because that is their lifeline.” If this is a valid observation—and I think it is—it shows the centrality of credit cards in our lives, a point I made in a recent op-ed, “Our Love-Hate Relationship With Plastic.” I also believe that, unlike the current foreclosure trend, the bankruptcy boom of a few years ago was a renters’ phenomena. Renters have no choice but to give up their credit cards. They are a lower income group who are more likely to be living in relatively inexpensive housing, and their debts are credit cards and other forms of commercial loans. Many of those who are now in trouble with their mortgages may be people whose incomes are not really sufficient to handle home ownership: homeowners who should be renters. But it is interesting to note that, for debtors who have a choice, walking away from the home and mortgage—as difficult as that decision must be—is often more attractive than giving up credit cards.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Priceless: Good Debt, Bad Debt

MasterCard has a new version of its Priceless advertising campaign in Condé Nast magazines. This long-running promotion is noteworthy for its attempt to encourage a very different attitude toward borrowing.

Once all lending at interest was taboo. The word usury was applied to any loan that required interest payments, and usury was prohibited by all the world’s great religions. Somewhat ironically it was Calvin and the Puritans who removed much of the stigma associated with lending, and today Islam is the only popular religion still maintaining that “Money does not beget money.”

But even as borrowing and lending began to come out from behind the veil of shame, there was a clear distinction between good and bad borrowing. Adam Smith, the 18th Century Scottish economist and father of classical free market philosophy wrote in his Wealth of Nations:

The man who borrows to spend will soon be ruined.

Until the early 20th Century, there was a clear distinction between “productive” and “consumptive” lending. It was considered acceptable to borrow money to purchase durable goods of lasting value or to invest in something that would bring future income, but borrowing money merely to spend was reckless and immoral.

I suspect that part of this view of good and bad debt stems from a wise assessment of human nature. Most consumptive acts pass quickly—long before the debt is likely to be repaid. In contrast the durable good or the income derived from investment lasts longer and stands as a reminder of the loan. The homeowner who enjoys living in her house each day pays her mortgage to sustain that enjoyment. Similarly, each time the college graduate gets paid, he has a reminder of the value derived from his student loans. In contrast, meals bought with a credit card are forgotten long before the bill arrives.

MasterCard’s ongoing Priceless campaign has sought to change our attitudes about borrowing in two ways. First, it promotes the normality of indulging in luxuries with images of people happily enjoying extravagances. These are not things we need; these are crazy imaginings of desire. The current Priceless Search campaign has people searching for their own priceless indulgences. The magazines include a heavy paper envelope stuck between the pages that contains a card—essentially a lottery ticket—that might mean you have won a wonderful, priceless indulgence. The prize offered in my New Yorker was a commissioned portrait of me painted by Julian Schnabel. My card said “Keep Searching” and told me that I had not won. I suppose I should go out and buy another magazine.

Perhaps most importantly, the Priceless campaign promotes the view that it is acceptable—even admirable—to use credit to pay for fleeting experiences. Taking your kids on an expensive outing is “priceless.” The other prizes offered in the Priceless Search campaign are a multi-continent culinary tour with noted chef David Bouley and a globe-trotting trip for two to explore the seven wonders of the world. Although these are contest prizes, the message is obvious. Indulgence is an acceptable way to use credit. Peek experiences are worthy goals and justifiable objects of indebtedness. Unfortunately, for many Americans Adam Smith’s words are more instructive. Borrowing to spend is—and has been—the road to ruin.

Monday, April 7, 2008

The Mortgage Crisis Morality Play

The foreclosure crisis has created a kind of Rorschach test of moral judgment. Different observers look at the same events and make very different assessments of fault and responsibility. Furthermore, more than any recent issue, the cutting point is social class.

If you search the Issues menu on John McCain’s website you will not find the words housing, mortgage, or foreclosure. Instead the candidate has an issue category called “Taxes & Economics,” and the title at the top of this page is “McCain’s Tax Cut Plan.” This is a dramatic contrast with both Democratic candidates who have extensive sections devoted to on the real estate crisis. However, elsewhere on McCain’s site you can find the text of his March 25 speech to Orange County Hispanic Small Business Roundtable, which reveals his moral judgment. Here is the crucial section:

A sustained period of rising home prices made many home lenders complacent, giving them a false sense of security and causing them to lower their lending standards. They stopped asking basic questions of their borrowers like "can you afford this home? Can you put a reasonable amount of money down?" Lenders ended up violating the basic rule of banking: don't lend people money who can't pay it back.

This is a remarkably carefully worded section. It appears to blame lenders—at least in part—for being “complacent” and signing up people who “can’t pay it back.” But who is the bad person in this narrative? The text makes it sound like the lenders’ only mistake was being too nice, which opened them up to victimization by unscrupulous borrowers. Lenders are guilty of “lowering their lending standards” to allow the riff-raff to buy homes. Further blaming of homeowners is evident later in McCain’s speech in a section on solutions:

In our effort to help deserving homeowners, no assistance should be given to speculators. Any assistance for borrowers should be focused solely on homeowners, not people who bought houses for speculative purposes, to rent or as second homes. Any assistance must be temporary and must not reward people who were irresponsible at the expense of those who weren't.

The mention of speculators is, of course, a red herring. It serves to make the victims of the housing crisis seem less sympathetic, and it will tend to discourage any relief programs. It gives the false impression that much of the current problem has been created by reckless speculators.

This kind of rhetorical strategy is reminiscent of the approach used by the banking industry during its long campaign to strengthen bankruptcy laws. In his signing ceremony statement for the 2005 bankruptcy bill President Bush said: “In recent years, too many people have abused the bankruptcy laws. They've walked away from debts even when they had the ability to repay them.” Of course, the overwhelming majority of people who filed for bankruptcy were suffering from a variety of real financial problems and were genuinely unable to handle their expenses. The focus on those who “abuse” the system strengthened the banking industry’s case but also misrepresented the problem.

McCain is using a similar victim-blaming strategy in the housing crisis. In his March 25 speech, the words “irresponsible” and “responsible” appear once each and in both cases they are used to refer to borrowers, not lenders. Don’t the lenders and the “speculators” in the securities market bear some responsibility?

Thursday, April 3, 2008

The Fake and the Real

The Bush Administration’s answer to the current housing and credit crisis is a fake solution. Although the new policies announced by Treasury Secretary Henry Poulson on Monday, March 31 have been widely reported in the media as “new regulation,” there is no new regulation. Poulson defended the current level of regulation of the banking industry and, instead, promoted the view that what we have here is a failure to communicate. A lack of interface among regulatory agencies. As a result, the administration has adopted what Paul Krugman calls “The Dilbert Strategy,” giving the appearance of responding by simply rearranging the organizational chart.

The Bush Administration has mastered the art of the fake response. Sometimes in the life of those in power, events demand an answer. There is trouble in the land, and the people look to their leaders for help. But President Bush and his group are advocates of small government and free markets, as a result, often they don’t really want to respond. In these cases they give the impression of caring by responding with BS. (See philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s On Bullshit)

Sometimes, if a response to a problem can serve his interests, the President responds with real, authentic policies. Examples include: tax cuts, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, bankruptcy reform, and the recent Wall Street woes. Fake policies include Katrina, the entire field of international diplomacy, the environment, and, most recently, the economic problems of the poor and middle class. Billions of dollars in loan guarantees—real money—is instantly moved into place when needed by the top end of the economy, but those who are losing their jobs and homes are still waiting.

Wednesday, March 26, 2008

Clear Differences on Foreclosures

The Republican and Democratic presidential candidates have always differed on a number of issues, but recent news has revealed a clear separation on how to treat foreclosures and the economy. According to statements reported in today’s NY Times, John McCain says he is not in favor of a vigorous government response to the mortgage crisis. In contrast, both democratic candidates favor programs varying between $30 billion (Clinton) and $10 billion (Obama).

In a statement that comes close to being a lie, McCain said yesterday “it is not the duty of government to bail out and reward those who act irresponsibly, whether they are big banks or small borrowers.” In truth, he seems only to believe half this statement. As documented later in the same article, McCain supports the Fed’s recent move to provide $29 billion in loan guarantees to support the Bear Stearn’s bailout. So, either the Bear Stearns episode was not a bailout in McCain’s view or rewarding those who act irresponsibly is fine, as long as they are wealthy investment firms and not mere citizens who are struggling to keep their homes.

Sunday, March 23, 2008

Drive-Through Windows, the Large Muscle Hierarchy, & Spending

The picture above was taken on March 17, 2008 at a local Dunkin’ Donuts during the lunch hour. Six cars in the drive-through line are visible from this angle, and none of them has yet to reach the speaker box where the driver can place an order. Also note the many parking spaces available for patrons ambitious enough to leave the car and walk into the store. The red car to the left is mine.

In Going Broke I suggest that physical effort is a major deterrent to many acts of spending and that the contemporary retail world has been designed to reduce the effort involved in spending. In particular, I propose the following Large Muscle Hierarchy:

- Sitting is better than walking.

- Walking is better than climbing stairs.

Cars put us at the top of this hierarchy. We are in the extremely desirable seated position, expending very little effort. Furthermore, we can move great distances in comfort and—when retail stores provide drive-through facilities—exchange money for goods and services. All without walking. The effects of all this convenience can be seen in our bank balances and waistlines.

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

Quick Help for the Powerful

The economic news over the last few days has been dizzying. On Sunday (!) the Federal Reserve Board announced a plan to lend money to Wall Street investment firms and approved a deal that allowed J P Morgan Chase to buy the failing Bear Stearns Company for pennies on the dollar. Today, the Fed announced yet another decrease in interests rates. Once again, Heaven and Earth move quickly—at great taxpayer expense—to help the wealthy and powerful who gamble in the stock market, but the wheels of government move much more slowly—if at all—for the less powerful who are losing their homes and jobs, are without adequate health care, or are burdened by enormous debt.

The Fed’s actions may have been important and completely justified, but there is something very wrong with this picture. The suffering at the bottom of our economy seems to get very little attention, while the ups and downs of Wall Street grab the headlines.

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Ben Bernanke, Kingmaker

Yesterday the stock market shot up over 400 points, the largest one-day gain in over five years. Why? Because Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve Chairman, offered up $200 billion in loans to the top 20 investment banking firms in the country. Banks have been caught in a credit crunch caused by the subprime mortgage mess and need liquidity—cash that can be used to make investments. The stock market got all excited yesterday and went on a big run, and as I write this the Dow is up again this morning.

I am struck by two aspects of this story. First, there is the dizzying power of being able to move such enormous sums of money with the flick of a wrist. In contrast, the $170 billion economic stimulus package was hotly debated before Congress and the President would sign off. Of course, the rebates of the stimulus package are permanent disbursements, and the Fed is offering loans. But the imbalance in oversight and accountability is daunting. Those who serve the banking industry can move government funds quickly and with impunity. Those who serve the individual consumer must summon a great effort to do so.

The second and most important observation is that the Fed’s action is another short-term fix. There is still great worry about underlying value of mortgages in the US, and Bernanke’s action is another demonstration of the government’s responsiveness when it comes to the quick fix. But there is far greater reluctance to take on the true causes of economic instability. Why? Because some of these problems are difficult to solve (e.g., health care) and the solutions to others will be attacked by the powerful banking and business interests (e.g., mortgage lending and credit card industry reforms, wage and job security increases). Unfortunately, I have little faith that free markets will correct the kinds of problems we face today. We need a serious change of direction, away from the highly leveraged consumer-driven economy of the recent past, and it is unlikely that change will come without strong leadership.

Saturday, March 8, 2008

Upside Down and Unemployed

The bad economic news just keeps coming...

An Epidemic of Negative Equity

The real estate bust has engendered a new catch phrase: upside down. To be upside down is to owe more on your mortgage than your house is worth—to have negative equity. The value of your home is always supposed to be higher than the amount of your mortgage, but as real estate prices have dropped, many people—particularly those who had little equity to begin with—have found themselves upside down.

This week we learned that 10 percent of homeowners now have zero equity or are upside down. Long before the foreclosure crisis began and before the label upside down had been introduced, this particular form of financial checkmate was anticipated in “The New Road To Serfdom: An Illustrated Guide to the Coming Housing Collapse,” a May 2006 Harper’s piece by Michael Hudson. [The article is here, but only Harper’s subscribers will be able get at it.] Of course, the worry is that any economic bump—and there appears to be no shortage of them—will bring disaster to the upside downers, and without any equity to lose, many homeowners will be tempted to cut their losses by walking away from their mortgages.

More People Out of Work

Speaking of economic bumps, Friday we heard that the nation lost 63,000 jobs in February, the second drop in jobs in as many months and a much larger drop than had been expected. The unemployment rate actually fell, from 4.9 to 4.8 percent, but that was a statistical anomaly. The unemployment figures only include those who are actively looking for work. They do not include people who would like to work but have lost hope and given up looking. This last group also increased in February, so joblessness overall is on the rise. If you put these two news items together—more homeowners without equity and increased joblessness—it seems likely that, at least for the near future, foreclosures and bankruptcy will continue to rise.

Tuesday, February 26, 2008

Still Going Broke

The week is just starting, but already the news has not been good for the American consumer. Yesterday CNN ran a story, “When Credit Puts You in Jeopardy,” which cited a Demos study showing that overall credit card debt grew by 315 percent from 1989 to 2008. In addition, CardTrack.com is reporting that the percentage of people who are delinquent on their credit card payments is the highest it has been in three years.

Then comes the news that foreclosures were up 57 percent in January over the same month last year. If there was any good news in this report it was that the month-to-month increase in foreclosure had diminshed slightly, but it is clear the foreclosure crisis will continue. Yesterday also brought news that sales of existing homes dropped for the sixth straight month and that prices are continuing to decline. As long as the real estate market is in free fall, more and more people will find themselves trapped in a house that is worth less than the mortgage. If they, like millions of others, get into a financial squeeze, selling the home to get out from under the mortgage will not be an option.

So many people are facing foreclosure that a new cottage industry has cropped up. You Walk Away is a web-based company that sells a “Protection Plan and Kit” to help homeowners through the process of foreclosure. Critics argue that this kind of business is changing consumers’ moral compasses and encouraging irresponsible behavior, but it seems to me that both irresponsible lending and irresponsible escape from obligation are the natural results of an unregulated free market system. The NPR site has a good story on this issue.

On the heels of these discouraging reports comes the news that two bills that would provide relief to holders of subprime mortgages are under attack by the mortgage industry. For a counterbalancing defense of the bills, see Elizabeth Warren’s most recent blog posting.

Finally, today CNNMoney.com is reporting that consumer confidence is at its lowest point in 14 years. In a consumer-driven economy that is very bad news indeed.

Meanwhile, as I write this the Dow Jones Industrials average is up 126 points (1.01%) on the day. Go figure. It seems to me that, more than at any time in recent history, consumers and investors live in two different worlds--worlds that are often in direct conflict. I will have more to say about this in a future post.

Monday, February 18, 2008

Something Happened in the 1970s: The Minimum Wage in Perspective

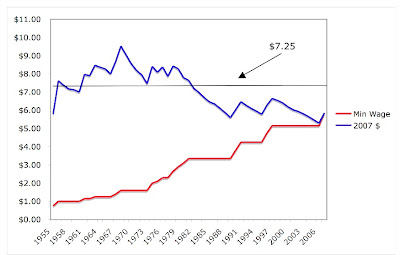

While looking at some data on the US federal minimum wage, I came across an interesting trend. One of the themes of Going Broke is that something happened in America beginning in the 1970s. The symptoms were dramatic increases in rates of bankruptcy and personal indebtedness that continued right into the 21st Century, but the causes of these signs of soaring of financial misery are far from obvious. I make a case for the combined effects of several modern pressures, and one of these is economic insecurity produced by declining real wages for many workers. Now take a look at the graph below, which I constructed a few days ago.

The red line of the graph shows the actual or “nominal” minimum wage for each year since 1955, and the blue line shows that wage, adjusted for inflation, in 2007 dollars. So, for example, in 1979 the minimum wage was $2.90/hr but it had the equivalent buying power of $8.28/hr today. The overall arc of the blue line shows that, here, too, something happened in the 1970s. From 1955 through 1968, the minimum wage rose sharply, peaking out at $9.53/hr (adjusted for inflation) in 1968, but since the late 70s, the minimum wage has been on a long and jagged slide.

Last year, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the Democratic congressional victory of 2006, Congress and the President agreed to a plan to increase the federal minimum wage. Under the new law, the wage will increase in each of three years, topping out at $7.25/hr in the summer of 2009. The graph shows that, when the minimum wage hits this point, it will bring us back to where we were in 1982, when the nominal minimum wage was $3.35/hr. Of course, this really overestimates the increase, because by the time the summer of 2009 rolls around, inflation will undoubtedly have increased, pushing the black horizontal farther down relative to the blue line.

Most states have set their own minimum wages at rates higher than the federal rate, but as this map from the US Department of Labor shows, there are 18 states (blue, red, and yellow below) for which the federal minimum wage applies, including Louisiana and Mississippi, the states most severely affected by Hurricane Katrina. Economists argue about whether increasing the minimum wage has the negative effect of increasing unemployment. But we know that income disparity has increased over the last three decades, and it seems likely that this trend in the federal minimum wage has been a contributing factor.

Thursday, February 7, 2008

Will We Begin to Spend Less and Save More?

A February 5, New York Times article “Economy Fitful, Americans Start to Pay as They Go” predicts the credit crunch and downturn of the housing market will lead Americans to use credit less and save more. Writer Peter Goodman points out that many people who have been spending out of their home equity will now enter a period of forced restraint. The free ride produced by rising real estate prices and easy credit has come to an end.

Without question, many who could spend freely in the past will now be constrained by lack of equity, but if credit card debt remains as widely available as it has, the basic problem—our spending-to-savings ratio—may persist. My mailbox still contains daily credit card solicitations, and at the mall I am regularly offered store credit cards. As long as the use of credit cards is so widespread, we are likely to have a continuing problem with debt. In a service economy dependent upon consumerism, many people will respond to the impulsive voice in their heads saying, “Put it on plastic,” rather than the wise one saying, “Don’t buy it. Save your money.”

In addition, saving has gone so far out of fashion that there are few social or economic incentives for holding on to your money. If we are going to wean ourselves from plastic and protect ourselves from the uncertainties ahead, we need to create easy mechanisms for putting income away and do a much better job of selling the virtues of a well stocked savings account.

Friday, February 1, 2008

Medical Innovation is the Mother of Health Care Necessity

Some things are just wants. Products or services that we would like to have—sometimes really like to have—but we know we can live without. Often these desires are created by product innovation. Steve Jobs introduces a new iPod or the iPhone, and suddenly we have wants we could never have imagined.

In The Overspent American Juliet Schor describes the gradual ratcheting up of needs. Home air conditioning was once considered a necessity by very few, but now fully 70 percent of us consider it a need. Because few of the old needs go away, technological advances create more “needs” that compete for our income. Just a few years ago, computers and cell phones were unheard of, and now they are must-have items.

But sometimes a new product becomes an immediate need. The minute it is introduced we have no choice but to buy it. This is particularly true for medical treatments. Health is the trump card. In Going Broke I give the example of Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering statin drug, that, once introduced, became an instant necessity for millions of Americans. In 2006 Lipitor’s US sales were 12.9 billion dollars, making it was the highest-selling drug in the world. If you have high cholesterol that you are unable to bring down any other way, your doctor is very likely to prescribe Lipitor or a similar drug, and most consumers will fill the prescription because they feel they must. You can’t take chances with your health.

Now the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has produced a report, “Technological Change and the Growth of Health Care Spending” showing that approximately half of the growth in US health care costs in recent decades comes from medical innovation: new treatments made possible by technological advances. Furthermore, the report concludes: “The nation’s long-term fiscal balance will be determined primarily by future growth in health care costs” (p. 17). This is a big problem fraught with ethical issues. How do we apportion medical services and who should pay? Medical innovation is a two-edged sword. It brings the hope of longer life and better health to many, but it also hungrily consumes more and more of our personal and national budgets. Where will this trend lead us?

Thursday, January 31, 2008

Rebate or Bonus?

In Going Broke,I discuss Nicholas Epley’s studies of how thinking differently about a windfall influences what we do with it. In a series of laboratory studies, Epley found that money described as a “bonus” was more likely to be spent than money described as a “rebate.”

A bonus feels like extra income, whereas a rebate feels like lost income that is being restored: a reimbursement. In “Rebate Psychology,” an excellent op-ed piece in today’s NY Times, Epley points out that the proposals for an economic stimulus package fail to take advantage of his findings. If politicians are hoping to encourage spending, they would be better off describing the $600 and $1200 disbursements as bonuses, not tax rebates. Thinking about money differently can greatly influence whether we hold on to it or let it slip away.

Epley’s research is a good example of what psychologists call a framing effect, but the larger question is, should consumers spend or save their rebates? Many Americans would be better off saving their rebates or using them to pay down debt. As a result, I am glad that Epley’s framing effects have been ignored in the current proposals. Spending a “bonus” might be good for the stock market, but for many consumers, saving the tax “rebate” would be a much wiser course of action.

Wednesday, January 30, 2008

Moral Hazard and the Costs of Foreclosure

Today the Boston Globe reports that the City of Boston will begin pressuring mortgage companies to maintain their foreclosed, vacant properties. Many of these deteriorating buildings are in violation of city ordinances, and when safety becomes an issue, the city is forced to assume the costs of boarding buildings up or—as in the case of one home—draining a backyard pool.

The costs of maintaining foreclosed properties can be thought of as a negative externality: an expense produced by the mortgage companies’ own behavior that is borne by someone else, in this case the citizens of Boston. To the extent that we blame the foreclosure crisis on the irresponsible practices of lenders who have ventured into the risky subprime market, we can say that these costs have been unfairly unloaded onto the city. Ideally, the banks should adopt lending practices that make foreclosure less likely and factor all the costs of foreclosure—including the maintenance of vacant properties—into their business plans.

Which brings us to the concept of moral hazard: the idea that people who are shielded from the risks of their own actions behave less responsibly. Moral hazard is often applied to consumer behavior. For example, one of the arguments against supplying health insurance is that it might encourage risky behavior and the unnecessary use of healthcare services. If everyone assumed all the costs of their health-related behavior (e.g. eating, smoking, and visiting the doctor) would they behave more prudently?

The proposed responses to the foreclosure crisis also bring up issues of moral hazard. For example, would a bailout of the mortgage lenders shield them from the consequences of their unwise lending practices and inadvertently encourage that behavior? (For a discussion of these issues, see the NPR story “Subprime Bailout: Good Idea or 'Moral Hazard?”)

The question of how policies encourage or discourage prudent behavior is a constant concern. In this case, Boston City Councilor Robert Consalvo will introduce legislation that would force mortgage companies to identify who is responsible for the maintenance of empty buildings, post contact numbers, and pay a $100 annual fee for each vacant property. It is unclear whether this plan would eliminate a moral hazard in the lending industry and promote more responsible lending practices, but at very least, the City of Boston is justified in redirecting the costs of maintaining vacant foreclosed properties back to the owners.

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

The Prisoner's Dilemma of Tax Rebates

In a January 27th post to her blog, Elizabeth Warren likens the American consumer to a battered athlete who is being asked to go back in and do it one more time for the economy. Spend to help us win the game again. The proposed stimulus package will give the athlete a boost by putting a few hundred dollars in his or her pocket. The analogy is apt, because for millions of tapped-out consumers, spending the tax rebate will just put off debt repayment and maintain their current level of vulnerability to unexpected expenses or any other bumps in the economic road ahead.

The stimulus package highlights the Prisoner’s Dilemma of our current economy. Spending is good for the economy as a whole, but saving is good for the individual consumer. We have over-fished the waters of the consumer economy, and too many individual citizens have been sacrificed in the process. Rather than spend their rebates—which, ironically, the federal government must finance with borrowed money!—Warren recommends that consumers use the rebate to pay off some of their debts. BabyBelle, a commenter to Warren’s post, says she plans to deposit the rebate in her rainy day fund. Both of these ideas are on target. The rule should be (a), if you have debt, use the rebate to pay it down or (b), if you are debt free but have little savings, save the rebate. On the other hand, if you have no debt and plenty of savings, do whatever you want with your rebate. Unfortunately, not enough Americans fit in to this enviable category.

These recommendations may not help the economy as a whole, but generally “the economy” is defined as the stock market—the current value of the portfolios of wealthy investors. When the market starts to drop, the economy is said to be taking a down-turn, and the media and politicians begin to pay attention. But for far too long the personal financial portfolios of individual middle class and poor consumers have been going south without raising an eyebrow. It is time these consumers ignore the call to bail out the rich investors and concentrate on what is best for their personal economies. Save your rebate or use it to pay down debt. Don’t spend it.

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Clinton & Singletary on the Economy

In a recent column entitled, “One Candidate and the Economy," Michelle Singletary, the personal finance columnist for the Washington Post, reports a conversation with Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. Clinton’s comments show that she is aware of the larger role of credit card and other commercial debt in the ongoing foreclosure crisis and general economic downturn. One of her most useful points is the need for financial education and improved financial literacy. Without blaming the victim, she recognizes that there is a serious problem of personal indebtedness and the need to help people get out from under.

This kind of article is not surprising from Michelle Singletary. She is one of the most level-headed personal finance advisors on the scene today. In a sea of useless financial advice, Singletary is an oasis of sound judgment.